Impact of GAA FETs Replace finFETs Transistors at 3/2nm Chip

[ABS News Service/05.03.2022]

The chip industry is poised for another change in

transistor structure as gate-all-around (GAA) FETs replace finFETs

at 3nm and below, creating a new set of challenges for design teams that will

need to be fully understood and addressed.

GAA FETs are considered an evolutionary step from finFETs, but the impact on design flows and tools is still

expected to be significant. GAA FETs will offer additional freedom to design

teams to optimize their designs because there is no quantization. With finFETs, quantization in the fins limits the ability to

balance drive current, leakage, and performance. As a result, different processes

are needed for wider devices, which boost performance, or narrower devices for

low-power applications. GAA FETs eliminate that problem.

The new gate structure sharply reduces current

leakage. At 7nm and 5nm, leakage in finFETs is

beginning to increase because the bottom side — the part connected to the

silicon body — is not fully controlled. This was a key reason why finFETs were introduced in 2011. With planar transistors,

even when a device was turned off, current would continue to flow between

source and drain. As a result, designers were forced to utilize such approaches

as power gating and other techniques to minimize wasted power.

But the transition from 2D transistors to 3D

transistors created significant modeling issues. There was a spike in the number

of parasitics that had to be considered. All told, it

took several years to fully work out the implications of this new device

structure, requiring significant changes in the development flow – particularly

for analog devices.

Now, finFETs are running

out of steam. At 5nm, finFETs are reaching the end of

their ability to shrink and still provide meaningful scaling benefits. The

number of fins has been reduced, and in practice cannot go below two. While fin

width can be reduced, fin height has to be increased to compensate. New

materials are being considered for the fin so that carrier mobility can be

maintained, but the writing on the wall is clear.

So the primary focus of the industry is bringing

the gate to the fourth side of the channel, creating a gate-all-around

structure. By raising the channel in the transistor and creating a fin, which

wraps the gate around the channel on three sides, the surface area between the

gate and channel is increased.

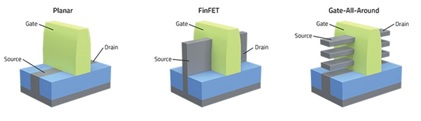

Fig. 1: Planar transistors vs. finFETs

vs. gate-all-around Source: Lam Research

Many articles have been written that describe these

new structures and how to fabricate them (Moving to GAA FETs, New Transistor

Structures At 3nm/2nm). The industry remains in a validation phase for the

models and design flows, which will be required for these new structures at 3nm

and below. Production is expected to begin in the 2022/2023 timeframe.

The impact

The good news is that the basic physics have not changed. The transistors still have all of the same elements as they always have. But their characteristics will improve, and some of the restrictions of the past will be lifted. It all comes down to the channel width. The wider the channel, the more electrons can flow and the faster the device can operate. But that allows for more leakage. A fully surrounded channel (sometimes called a nanowire) makes it difficult for electrons to escape. By stacking multiple nanowires on top of each other, you can have elements of both. Each wire can be tightly controlled, and multiple wires operating in parallel provide superior drive capabilities.

How big a disruption will this be for designers? “FinFET was the first device in the third dimension and

there were a lot of parasitics around the Z

dimension,” says Dusan Petranovic,

principal technologist for Siemens EDA. “That was a big change. But

gate-all-around (GAA) is more evolutionary. Even though there are a lot of

changes, foundries believe that 90% of the process can be re-used and the BEOL

has not been changed much. Nanosheets are also 3D,

and there can be 3, 4 or 5 nanosheets. Even though it

is a 3D structure, we can approximate that like a planar structure with the

variable width of the sheets. People know how to approach this from an

extraction point of view.”

Parasitic extraction is one the main areas that is

impacted. “Essentially, it’s all about accuracy at this point because smaller

transistors mean smaller wires, and the routing of these wires will be compact

and crowded, impacting capacitance and the coupling capacitance between the

wires,” says Hitendra Divecha,

product management director in the Digital & Signoff Group at Cadence.

“Smaller transistors have to be modeled accurately — we are talking about attofarad (aF)

and almost 3D field solver-like accuracy for these parameters. For MEOL (middle

end of line), due the proximity to the device itself, there will be new

modeling features that will have to be implemented to accurately capture the

impact on the timing of standard cells and EMIR. Besides parasitic RC values,

RC topology will also matter for extraction accuracy.”

It is a progression. “They know what questions to

ask,” says Carey Robertson, director of product management for Siemens EDA. “We

had multiple generations of planar technologies, and as you went from planar to

planar you knew what to ask. Now we’ve had a generation of 3D transistors that

spawned a whole new group of questions, and so designers know what they need to

investigate and to make sure they understand how it’s going to operate.”

With GAA FETs, performance is expected to improve

by 25%, with power consumption reduced by 50%. With finFETs,

both numbers have been roughly in the 15% to 20% range.

The addition of the gate on the fourth side

provides more control. “The electrostatic controls on GAA and Vts are much more controlled,” says Aveek

Sarkar, vice president of engineering at Synopsys. “This is important because

at the smaller nodes we are seeing significantly more variability, especially

for SRAM. So with GAA, we expect some of those to get more contained. But the

variability and parasitic effects are going to be significantly higher.”

In addition, some of the problems introduced by finFETS will be relaxed. “You have the possibility to

continuously vary the width of the nanosheet,” says

Siemens’ Petranovic. “They can now be sized

appropriate for different applications. If you need high switching speed, you

might want to use wider nanosheets for more current.

If you are designing SRAM cells, you may be more concerned about the area

footprint. Libraries will be developed to explore this new degree of freedom.

With finFET, we had discrete steps — 1,2,3 fin scaling. Now we can vary it continuously, and that

new degree of freedom has to be exported into various tools like synthesis and

place-and-route. There may be some parameterization of library cells to be able

to optimize designs better.”

New challenges

With change comes uncertainty. There is even more potential for variability in these new devices. “This will be a bigger concern than in the past,” says Petranovic. “Part of it is just because you have smaller dimensions, and you have to deal with the effect of line-edge roughness and thickness variation. There will probably be new equipment that is used for this purpose. We will use EUV for edge roughness control, but still it will be a challenge.”

Line edge roughness is a factor because this can

impede the flow of electrons. A new source of variability will be nanosheet thickness variation (STV). This causes variation

in quantum confinement that impacts performance.

There are other changes, that

while not directly to the GAA transistors, could be considered collateral

damage. “We see the decreasing supply and threshold voltages, and the

non-availability of thick oxide devices that result in transistors with lower

breakdown voltages,” says Andy Heinig, group leader

for advanced system integration and department head for efficient electronics

at Fraunhofer IIS’ Engineering of Adaptive Systems

Division. “That means transistors for classical output or driver cells aren’t

available in such technologies. So chiplet approaches

become necessary, where the GAA part is only responsible for the digital part,

and other components in older technology nodes that can realize the

input/output interface.”

Some analog components may still be necessary. “The

industry will have to figure out how to do analog design in these processes,

because anything interesting is going to have some analog content,” says

Robertson. “That will probably have to be at higher voltage. The digital VDD of

these chips will certainly come down, but there will be different voltage

regions to accommodate other design styles.”

Challenges remain, though. “The finFET

forced quantization, and that highly impacted analog circuits,” says Synopsys’

Sarkar. “That flexibility will become a lot more helpful in terms of what they

can and cannot do. But there are things that are going to become more

challenging. With the 3D topology, in terms of the capacitive and resistive

models, are the scalable rules that we have historically used going to be

sufficient and accurate for analog circuits? Do you need to have a different

approach to getting the parasitic, especially at the local interconnect level?

And how many RC parameters did you get?”

Other things are impacted just by scaling. “The

cross section of the wires is smaller,” says Petranovic.

“That means a significant RC delay increase, which is a potential bottleneck,

and there are a lot of techniques trying to avoid this. One is to introduce new

material for BEOL and even for MEOL. There is the introduction of air gaps for

intermediate layers. There are schemes for reducing VIA resistance.

Source/drain contacts are seeing increasing resistance. They have a notion of

self-aligned gate where they are trying to put contacts directly on top of

active devices.”

These changes will drive new kinds of analysis.

“Thinner wires coupled with stronger drive strengths means we have to think

about EMIR drop for MEOL — those wires that are very close to the transistor,”

says Robertson. “Traditionally this was only done at the full-chip level and

for power distribution.”

Again, these are incremental concerns. “There is no

indication that additional layers will be introduced like we had when we made

the jump to finFET with local interconnects and

additional vias, which then translated into an

explosion in parasitics,” says Cadence’s Divecha. “There will always be third-, fourth- or even

fifth-order manufacturing effects that parasitic tools will have to model for

accuracy purposes, so there will be more BEOL modeling that will have to be

enhanced to ensure the impact on both timing and EMIR is minimized. There may

be additional routing rules that will have to be done for place-and-route.

However, from an extraction standpoint, the extraction of metal layers will

continue to exist as they do today for finFET

designs, but the focus will be more on accuracy and capacity.”

Power delivery network

Another area that almost certainly will be impacted is the power delivery network. Traditionally, this has been located in the metal stack built on top of the substrate.

PDN problems are growing. “The biggest problem with

the PDN is the RC effect — Ohm’s Law degradation,” said Sarkar. “Then, there is

the inductance effect. When you brought the chip and the package together, the Ldi/dt effect started to become

high impact. Foundries started to provide more advanced decoupling capacitors,

in addition to providing device level capacitors to suppress some of the noise

and get a smoother supply noise profile. The challenge, especially with GAA, is

you’re going to be packing a lot more devices in a square millimeter, and they

are going to be switching more frequently. So is there some way you can short

circuit and provide the current to the devices in an alternative manner?”

There are other power-related challenges, as well.

“The decreased supply voltage can only be realized by an extremely stabilized

supply network,” says Fraunhofer’s Heinig. “Different approaches are being discussed, such as

on-chip regulators, backside supply using TSVs or different stacking options.”

What are back-side power supplies? “The idea is to

move the power and ground wires beneath the transistors – on the back side,”

says Petranovic. “Then through-silicon vias are used to supply power to the active layers. This is

to reduce IR drop and noise on the signal wires, and to reduce congestion.”

That potentially adds a new form of analysis. “You

now have back-side metal,” says Robertson. “Previously, you put the transistors

on the substrate, and you pretty much ignored electrical effects between

transistor and substrate. You did some rudimentary modeling. Now you

essentially have transistors in the middle of lots of wires, instead of just at

the bottom. That should reduce noise overall, but if you have a noisy power

grid, you now have significant power grid interaction to the transistor. You

will probably need analysis tools to validate the noise contribution of the

power grid to the transistor, whereas previously the power grid would be on

metal layers 13 and above, quite a bit of separation from those devices.”

This adds a new issues. “What kind of stress does

this create?” asks Sarkar. “You have to supply the power on a regular interval

over to the devices. You will create additional layers of stress in the

silicon, and how you model some of that will become pretty critical.”

New models

Getting the right models is important. “Every new node gets more complicated and adds new technology effects have to be modeled,” says Petranovic. “EMIR, thermal, reliability, electomigration – all of these will get more complicated, but that would happen anyway just with scaling. For the device itself, it depends how accurately we need to model it. You have nanosheets vertically stacked, so the question is – can we approximate that to be something similar to planar with some vertical effects, or do we need to go inside the structure and extract some components? The right answer is to find the minimum detail necessary to accurately analyze the impact on performance.”

Getting it right is often an iterative process.

“It’s not just the model themselves,” says Sarkar. “It’s also process

development and device creation, which is where you have the transistor

architects, the process integrators feeding into the people who are doing the

first libraries, who are creating the first ring oscillator to see this is

coming together and getting an early preview of how a block is going to look

like. Finding out if there are certain things that we should be doing. The

notion of Design Technology Co-Optimization is becoming even more important.

How are we able to influence the various pieces that have resided in different

teams within organization? If they are in different organizations, it’s even

more challenging. How are we able to bring them together to have an early

preview of these effects, and provide feedback to the process engineers and the

architects on the left hand side of the equation, to help them help the right

hand side in a more efficient manner.”

Without the appropriate level of accuracy,

engineers have to over-margin their designs. “Today’s designer might need an

extra 2-4 months to close the signoff loop,” says Divecha.

“Extraction is a critical step in the signoff loop and we’ve heard from designers

that while the extraction runtime varies based on design sizes and types, full

flat extraction at these advanced nodes can take up to three days with some

extraction tools. This puts an enormous amount of pressure on designers to

achieve design closure in a timely manner to meet time-to-market pressures.”

The industry is currently trying to validate those

models. “There’s two parts to this: one is developing the model, and then there

is the analysis around it,” says Robertson. “Going from planar to finFET, to gate-all-around, there are new effects that need

to be modeled, and I don’t know that we have quantified all of them. Using an

example from the past – we didn’t care about proximity of planar transistors to

wells. Around the 20-nanometer node, that became an important physical effect.

I think we have an overall understanding of what needs to be modeled, but we

need more test chips, more experiments to make sure that we’re capturing all of

the physical effects in the model and once we do that, we can have analysis

tools in place. The industry is going through a validation exercise.”

There is more to learn. “This has to happen as

foundries and EDA vendors focus on making these types of devices mainstream,”

says Divecha. “Having said that, whether you are

doing digital designs or custom/analog designs, most of these requirements will

be taken care of by EDA software, specifically extraction tools, and all the

effects will be captured in foundry-certified techfiles.”

Conclusion

At this point in time, each of the foundries is looking at a range of possibilities. But based on early announcements, it would appear that there may not be a lot of commonalities between them. Each will have to work out which methodology works best for them and what provides the best yield.

Time will tell what will be the most successful.

But the “good” news is that scaling is likely going to be the larger cause of

pain, and not the change in structure of the transistors.